If your fleet’s sleeper trucks idle more than 1,000 hours a year, it’s time to ask yourself if you, too, have remained idle too long. At the very least, shift into low gear and run the numbers on idling costs versus the total cost of ownership for an auxiliary power unit, or APU.

There are several different options to reduce idling, ranging from diesel-powered and electric APUs to bunk heaters and OEMs’ battery-powered HVAC systems. Even in the specific long-haul segment, the ROI for each can vary greatly from fleet to fleet, as can the various hotel loads. One driver might only need climate control and juice to run the fridge, while another powers a microwave, television, and gaming system. In addition, those who suffer from sleep apnea may need a CPAP machine, which can consume up to 800 Wh at max setting.

But you can find the best fit with a few calculations and a review of the latest North American Council for Freight Efficiency Confidence Report, titled The Idle-Reduction Playbook: Operational Strategies for Modern Trucking Fleets.

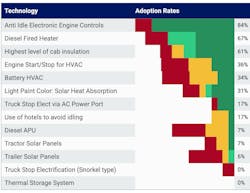

NACFE researchers assigned ROI estimates and testing guidance for a variety of options, including:

- Diesel APUs

- Electric APUs

- Fuel-operated Heaters

- Fuel-operated Coolant Heater

- Intelligent Engine Management Systems

- Thermal Management Systems

- Vehicle Controls & Driver Behavior

The Confidence Report exhaustively details the many idle mitigation solutions, but one thing is clear: They all provide maintenance and cost benefits versus leaving the engine idling all night. On APUs, specifically, NACFE has found that advances in APU technology and other anti-idle products have made them more attractive than letting a Class 8 sleeper’s engine run throughout an extended Hours of Service rest period.

“We are currently at a technological and economic inflection point,” Dean Bushey, the report’s lead author, told Fleet Maintenance. “Fuel remains the second-largest operating expense for fleets, accounting for 20% to 25% of total costs.”

Wear and tear also increase, leading to additional downtime and repair expenses.

“Component failures are also more likely to happen sooner due to that extra idling time on the engine,” said Sid Gnewikow, APU portfolio leader at Thermo King, a provider of both diesel and electric APUs.

Furthermore, several states have adopted idling restrictions for buses and trucks, ranging from no idling in Washington, Idaho, and Illinois to five minutes or fewer in California, Pennsylvania, Florida, and New York. To find out what the restrictions and fines are by state and county, use the U.S. Department of Energy’s database, IdleBase.

Due to these reasons, “idle reduction has moved from a fuel-saving ‘extra’ to a core economic necessity for many modern fleets,” Bushey, NACFE’s director of programs, said.

As with any onboard technology, though, what saves money and cuts downtime for one fleet or route might have the inverse effect for another. And a technology that failed five years ago might be mature enough to succeed today.

Fleet managers will have to figure out a lot of this on their own, but we’ve collected several best practices and updated learnings on the many anti-idle options out there to help get you moving in the right direction.

Idling vs. APUs

Idling burns about 0.8 gallons per hour, based on Department of Energy data, which equates to 8 gallons per 10-hour rest period, or around $30 per night with average diesel costs hovering around $3.50/gallon. Annually, this cost can rise above $6,000 when idling around 1,800 hours per year, NACFE noted.

NACFE estimated that when such fleets purchase and install a diesel APU, they see an ROI in 12 to 24 months. Various industry surveys have placed sleeper adoption of diesel APUs at around 40% in 2010 and 55% in 2010. With an all-electric APU (eAPU), assuming diesel is at $4/gallon, the fuel savings alone pay for the device in 18 to 30 months. Incentives and factory-ordered options can shorten that ROI period to under two years, the report stated.

At 0.2 gph (under a moderate load), a modern diesel-powered APU burns a quarter of an idling engine, according to NACFE. An eAPU doesn’t burn any, although a modest amount of idling may be necessary to keep the batteries charged. And in freezing temperatures, drivers will likely idle to warm up the engine to prevent cold start wear and heat and defrost the cab. Certain diesel APUs can integrate into an engine block heater, and in open-loop systems, they can share a radiator with the engine to prevent cold starts.

On the maintenance side, the generally accepted rule is that an hour of idling is equivalent to at least 25 miles of driving. If idling 10 hours a day, 300 days a year, that’s like putting another 75,000 miles on the truck engine. That’s another oil drain or two per year.

Fleets should also consider the impact of excessive idling on a truck’s aftertreatment system. Based on Green APU’s online savings calculator, 3,000 hours of idling per year adds roughly $2,400 worth of aftertreatment-related costs. NACFE estimated $600 to $2,000 for DPF maintenance, as idling creates more clogging and forced regeneration. Maintaining a diesel APU can cost $300 to $600 per year for PMs such as oil and filter changes.

“If your shop isn’t trained to service diesel APUs as rigorously as the tractor itself, the ROI will evaporate,” Bushey said.

However, of the 14 fleets that participated in NACFE’s 2024 fuel study, about 14% reported using diesel APUs, while only 7% said they currently used them. Bushey explained that the overall low penetration reflected how day cabs comprised the majority of these fleets, though the amount that discontinued diesel APUs showed that undermaintenance, improper spec’ing, and lack of driver buy-in can doom a successful deployment.

lectric APUs don’t require nearly the same routine maintenance, needing only some cleaning and inspections. They typically have a higher upfront cost. The latest generations benefit from battery advances that allow them to last even longer and improve their ROI.

“We are seeing a resurgence in eAPUs, but they won’t entirely replace simpler methods,” Bushey said. “Lithium eAPUs now provide 10 to 17 hours of cooling with zero engine maintenance.”

He suggested pairing an eAPU with a bunk heater, which “at an installed cost of $1,000 to $2,000, they pay for themselves in months by saving roughly 85% to 90% of winter idle fuel.” For summer cooling, you turn on the eAPU.

Another option for fleets is finding a truck parking spot with a shore power hookup. The problem is only 2,000 of these electrified spots exist and are spread out across 100 to 150 facilities, Bushey noted.

In general, Bushey’s rule of thumb for any solution to avoid a failed deployment is: proper spec’ing + driver buy-in + rigorous maintenance.

“Tech that drivers find complicated or unreliable won’t be used,” he concluded. “The best results come from combining tech with training and incentive programs that align fuel savings with driver comfort.”

About the Author

Gregg Wartgow

Gregg Wartgow is a freelancer who Fleet Maintenance has relied upon for many years, writing about virtually any trucking topic. He lives in Brodhead, Wisconsin.